The

Highway

to Europe

in a rural Dutch village.

seized in Barcelona.

home outside Mexico City.

cocaine, which spanned continents,

cultures, and cartels.

The new criminal order

Think of the drug trade, and you might think of rigid hierarchies run by drug lords like Pablo Escobar or Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán.

Today, the reality is far more complex.

With global cocaine demand surging, and markets growing fast in Asia, Africa, and Europe, the days when a single cartel could dominate a whole supply chain are gone.

It is now far more likely for networks of gangs to link up, often on a sort of freelance basis, to move cocaine along different legs of the journey.

To see how this works in practice, OCCRP and its partners looked into how a group of gangs and criminals worked together to feed one of the world’s busiest drug highways:

The business model comprised a loose and likely fluid confederacy of Colombian, Mexican, Spanish, Dutch, and other criminals, working side by side to allegedly conceal, transport, process, and sell large volumes of cocaine.

Police said this group moved drugs for over half a decade before authorities stepped in to bust up their operations in 2020. More than a dozen people who allegedly took part have since been arrested in Latin America and Europe.

Many questions are still unanswered. Even after years of cross-border investigations, police were not able to say who, if anyone, was ultimately the collaboration’s main driving force.

But reporters managed to uncover rare details about its operations thanks to documents found in a leak of emails from the Colombian prosecutor’s office, corroborated with court records, police reports, company records, and interviews. (For more stories based on the leak, click here.)

The findings show how the drug trade has opened up in recent years to smaller groups and local players, who frequently collaborate with each other as well as with larger cartels, bringing specialized skills to different stages of the smuggling process.

This trend — driven by new communications technology, the globalization of the drug trade, expanding markets, and the fragmentation of formerly monolithic groups — has made it more complicated than ever to crack down.

European police have likened modern-day organized crime structures to the mythological nine-headed Hydra, who could regrow two heads for every one that was cut off.

“Removing one head does not kill the monster,” the EU’s police agency, Europol, said in a 2021 report.

Grown

The cocaine that eventually wound up in the Netherlands started its journey in Colombia, where the U.N. says that more than two-thirds of the world’s coca leaves are grown.

Police say the coca was sourced from the southwestern department of Putumayo, a border area that is one of the country’s top producers — and a hotspot for rival trafficking groups.

Coca cultivation has been on the rise in Colombia, as well as in Peru and Bolivia, for the past decade. A major surge in 2021, coupled with advancements in farming techniques, sent global cocaine supply to record highs.

The splintering of groups who once monopolized the trade has meanwhile spurred a more competitive, “free market” environment that likely made growing and processing cocaine more efficient, the U.N.’s drug and crime agency says. (For more on these trends, read Cocaine Everywhere All at Once: How Drug Production Is Spreading Into Central America, Europe, and Beyond)

This fragmentation also opened up opportunities for gangs from outside Colombia, whose cartels once dominated the narcotics trade from source to sale.

Police say the trafficking collaboration traced by OCCRP, for instance, was controlled in large part by a crime group from Mexico.

The Mexican group’s exact identity remains murky. Spanish police first identified it as the Beltran Leyva cartel, but reporters were not able to independently verify the claim.

What is clear, police say, is that the group maintained a Colombian connection through an allegedly experienced trafficker named Jean Paul Hoyos Bohorquez, alias “Sodapuppy.

Drawing on information from Dutch prosecutors, Colombian police alleged that Hoyos Bohorquez was a “principal coordinator” of the cocaine shipments overseas, and supervised the final stages of production and sale in the Netherlands.

Much about Hoyos Bohorquez’s past is still unknown. Reporters could find no previous convictions, investigations, or other evidence of his involvement in drug trafficking. Hoyos Bohorquez’s lawyer said it would be “impertinent and imprudent” to comment on the police claims, because they were subject to an ongoing investigation. Citing his client’s right to privacy, he stressed Hoyos Bohorquez was innocent until proven guilty.

Hoyos Bohorquez was arrested in July in Colombia. The process to extradite him to the Netherlands, where he faces drug trafficking and money laundering charges, began this year.

On their way from Colombia, the drugs did not necessarily travel directly to their final destination. Traffickers often follow the path of least resistance, bending towards allies and away from law enforcement.

In this case, the first stop would be the home country of the group that commissioned the shipment: Mexico.

Mexico

Mexican cartels, who once served mostly as cocaine couriers, are now often wholesale suppliers. While they typically supply the U.S. market, recent drug busts show they have also been making inroads into Europe, thanks to cooperation with Europe-based criminal networks.

This was the case in the collaboration traced by OCCRP. After securing cocaine from Colombia, the Mexican crime group then allegedly ferried it — along with large quantities of methamphetamine — to partners on the other side of the Atlantic, according to a Spanish police investigation.

Like the vast majority of cocaine seized in Europe, the drugs were sent via shipping containers. In recent years, traffickers have devised sophisticated methods to conceal narcotics, ranging from sneaking it into boxes of legal goods to hiding packages in the walls of the containers themselves.

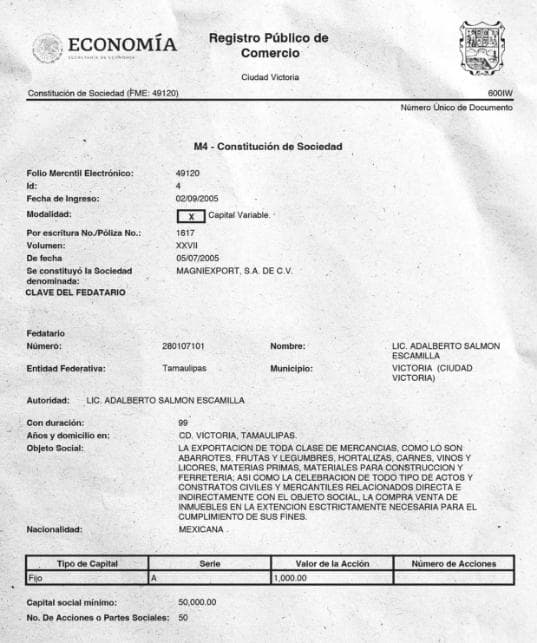

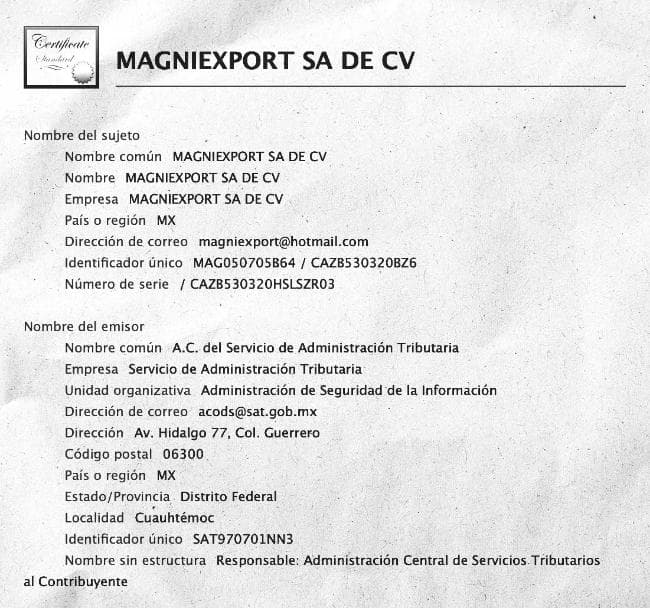

To provide cover, the Mexican group allegedly worked through a local export company called Magniexport S.A., which often ran a maritime route from the Mexican port of Veracruz to Barcelona.

Spanish police described the company as being "at the disposal" of the crime group, but did not add more details. Mexican corporate records show the company is owned by two Mexican nationals, but reporters were unable to find any other relevant details about them or any record that Magniexport has been investigated in Mexico. The company did not respond to requests for comment.

The drugs were stashed in hidden compartments built into a type of concrete blocks used for construction.

According to the Spanish police report, the method was effectively “undetectable” by port controls, and demonstrated the “high technical capacity of the Mexican cartel” as the blocks appeared custom-built to conceal the drugs.

It is still unclear who was ultimately behind these operations on the ground in Mexico.

With roughly 150 cartels, the country’s criminal world is in a state of regular flux. Many of today’s gangs are “fragmented remnants of former larger organizations that constantly shift their alliances and fight over territorial control,” according to the U.N. drug agency.

On the other side of the Atlantic, however, the alleged players would become more clear.

in Spain

Between 2011 and 2020, Magniexport sent several dozen shipments of concrete blocks to Barcelona, trade data shows.

The trafficking group tried to maintain a “legitimate” business and set up “safe import channels” by sending some shipments of drug-fee blocks that they could sell to local companies, Spanish police said. But this proved difficult since the material was expensive and not widely used in Spanish construction.

Magniexport’s legal representative in Spain, who has dual Spanish-Mexican nationality, was arrested on drug trafficking charges along with three others. The case is still awaiting trial.

After so many years of success, two alleged members of the trafficking network were surprised by the Barcelona bust, according to encrypted messages cited by Dutch prosecutors in a request for assistance sent to their Colombian counterparts.

Only the drug-free blocks would stay in Spain, a Spanish Civil Guard officer who participated in the investigation said. The others would be sent to the group’s other key European base: the Netherlands.

The Netherlands

A rural Dutch village of fewer than 2,000 people, Poortvliet is home to broad bicycle paths, a windmill, and a small church.

One night in late March 2020, this bucolic scene was disrupted when a barn burst into flames, killing dozens of sheep and lambs and unleashing a noxious smell, according to a Dutch police officer who investigated the scene.

BARN FIRE”

The intensity of the flames and the chemical remains left behind quickly made it apparent that “‘Hey, this isn't a normal barn fire,’” recalled the officer Freek Pecht, an anti-drugs coordinator.

When a crane pulled a large boiler out of the shed’s charred remains, it was clear the site had been what Dutch authorities call a “cocaine laundry” — one, Dutch prosecutors said, where Hoyos Bohorquez played a “leading role.”

Coca leaves must go through a series of chemical transformations to become cocaine hydrochloride, the powdered form sold to users. This process has traditionally taken place in South America.

But facilities to carry out the cocaine manufacturing process have increasingly been cropping up in Europe, particularly in Spain and the Netherlands.

One reason for this is the rise of more chemically advanced methods to conceal cocaine inside legal goods. In some cases, traffickers have drenched products such as clothing or charcoal with cocaine “base,” a rawer form of the drug, which must then be extracted and processed in Europe upon arrival.

The Poortvliet lab was set up to do exactly that.

The encrypted chats cited by Dutch police show that Hoyos Bohorquez and a Mexican colleague, Alonso Alverdi Benavides, alias “Corncrusher,” were in the Netherlands to oversee the drug’s production, while keeping in touch with bosses back in Latin America.

According to Dutch prosecutors, two Dutch nationals also played a senior management role, and allegedly gave Hoyos Bohorquez 130,000 euros to set up a new facility after the first lab burned down.

Once processed, the cocaine was sent on to both Latin American and Dutch members of the network, who distributed it in the Netherlands — always, Dutch prosecutors said, “in large quantities.”

in

With cocaine going for more than $40,000 per kilogram in the Netherlands, cash inflow was high. Encrypted messages intercepted by police provide a glimpse of the group’s earnings.

While still in the Netherlands, Alverdi Benavides sent administrative lists to a Mexico-based figure Dutch prosecutors could not identify beyond his EncroChat username.

The list covered payments and drug sales from the previous three weeks, noting that Hoyos Bohorquez had received almost half a metric ton of cocaine valued at 24,000 euros per kilogram, and remitted roughly 8.5 million euros over the same time period.

According to Dutch investigators, Hoyos Bohorquez allegedly sent the funds directly or through third parties to recipients in “Colombia and/or Mexico.”

Over four months in 2020, they said, he allegedly remitted some 18 million euros, including through a “token system” whereby the recipient uses the serial number of a banknote as a “key” to pick up the money.

Members of the network allegedly sent more cash back to Mexico via Spain. A Spanish investigation found that “large sums” were transferred from the United Arab Emirates and Hong Kong to Mexico through the bank accounts of Spanish companies.

According to the Spanish police, local businessmen had helped to obscure the origins of the money by using bank accounts of Spanish companies for transfers, “which in all probability were the product of drug trafficking.” This investigation is ongoing.

Authorities have not said who was on the receiving end of the transfers.

But Alverdi Benavides has been separately scrutinized for his connections in Mexico. In March 2022, he was arrested during a raid on a luxury home outside Mexico City, where police were searching for an alleged Colombian drug lord, Eduard Fernando Giraldo Cardoza, known by his alias “Boliqueso,” a Cheetos-like snack.

Alverdi Benavides was released due to abuses committed during the raid. He and Boliqueso did not reply to requests for comment.

Reporters found that Alverdi Benavides had also done business with a Mexican financial firm, Black Wallstreet Capital, which, according to a spokesperson for Mexico City’s prosecutors office, has come under federal investigation for “irregular” transactions and possible money laundering. Federal prosecutors did not respond to a query about the status of the investigation.

When reached for comment, Black Wallstreet’s owner, Juan Carlos Minero Alonso, told OCCRP that Alverdi Benavides and his relative had approached the company to “manage what they said was wealth obtained in the cargo transportation and cement construction sector.”

“Today, it’s clear they had intended to pass off their resources as legal by seeking to do business correctly with respectable and recognized business partners," he said, adding he had ended any relationship with Alverdi Benavides more than two years ago because he did not like his "lifestyle."

Minero denied having any involvement with alleged criminality, adding, “I led a legal entity, that paid taxes, that carried out regulated activities and with total transparency.”

Jorge Lara, researcher from National Institute of Criminal Sciences, said the lack of a healthy reporting system meant money laundering investigations often hit dead ends in Mexico. Between 2018 and 2022, just seven out of 752 money laundering cases referred to the attorney general’s office and other fiscal authorities were actually prosecuted — under one percent.

“Organized crime is celebrating," Lara said. "Both for their [criminal] operations and the amount of resources they are moving.”