The Russian occupation of Bucha lasted just 33 days — from late February to April 1 this year — but it has already become a byword for brutality.

Mass murders of civilians there made headlines around the world. Journalists and officials rushed to the Kyiv suburb to interview survivors and gather evidence that war crimes had been committed.

But what was it really like to live through those 33 days of occupation?

OCCRP and its Ukrainian partner Slidstvo.Info obtained the logs of a Telegram chat used by 88 people from a single apartment building in Bucha, known as Block 17.

The block was built in the waning days of the Soviet Union to house the employees of a glassworks across the street. Many older residents still know each other from those days, when they worked together producing glass pipes and windows at the factory on Yablunska Street, a major thoroughfare that cuts a diagonal swath through town.

Bucha lies 25 km west of Kyiv. Block 17 is in the southwest of the city, in an industrial area.

Before the war, the Soviet-era housing block was home to several hundred residents.

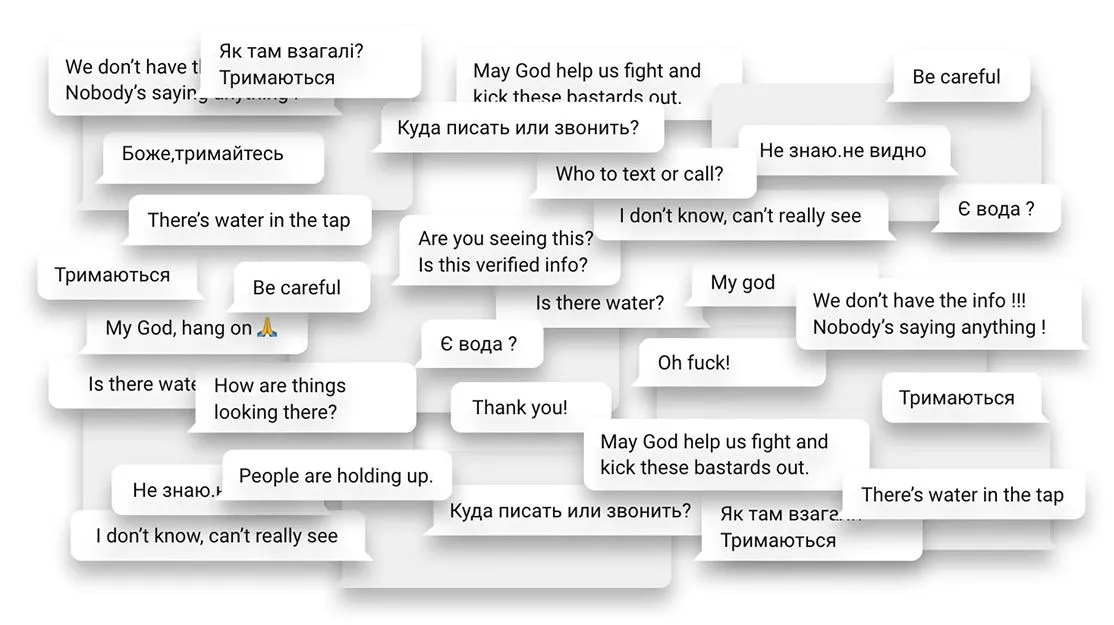

In March and April, as they grappled with the indignities of war — being shot at in the streets and in their homes, having to scrounge for firewood and fresh water — they sent thousands of text and voice messages to each other, along with photos, memes, and videos, creating a unique snapshot of life under siege.

The chat logs are messier than other wartime narratives. The view from Block 17 could be parochial, scattered, confused, and occasionally profane, as residents desperately tried to piece together an understanding of what was happening around them.

Bombings, gunfire, and constant fear were interspersed with panic, grinding boredom, and neighborly bickering, but also cooperation and commiseration.

“Those of us who stayed have a close relationship, as if we crossed the ocean or survived an earthquake,” said Iryna Karpenko, a former glass factory worker who has lived in Block 17 for nearly four decades.

Before the war began, she said, “We didn’t know how well we lived. And we were grumbling all the time, didn’t want to go to work.

“My God! I’d rather go to work than see things like that!”

Russian tanks rolled into Bucha on February 27.

The residents of Block 17 came face to face with war.

The upper floors of the block were severely damaged after the fire on March 5.

In May, reporters visited the block to get a better sense of what actually happened during some of the events that dominated the chat.

They spoke to residents and got permission to reproduce their chat logs here. (Those who could not be reached, or asked for their names not to be used, were assigned pseudonyms. Some chats were condensed for clarity.)

For Mykhailo, a retired glassmaker, the fire followed a string of sleepless nights. He had stopped even bothering to go to bed. Instead he would just doze fitfully on his couch at night, fully dressed, with his cat Jack curled at his feet.

“At night, it was impossible to sleep. You’d doze off and you’d immediately hear that ‘boom!’”

On the afternoon of March 5 he was back on the couch with Jack, trying to get some rest. He had just nodded off when the shell hit.

“I opened my eyes. I couldn’t see anything. The plaster had fallen off. The ceiling had collapsed. Luckily, I have a habit of sleeping with my mouth open — otherwise my eardrums would have ruptured.”

Mykhailo

Mykhailo shows a picture of what’s left of his apartment.

Mykhailo was able to make it out of his apartment and save another resident from the flames. Together, they worked to put the fire out with sand.

Then he attended to other important matters — like tracking down Jack the cat, who had bolted after the first shell dropped.

His daughter tried to help by messaging the Block 17 Telegram group.

Reunited with Jack, Mykhailo took a philosophical approach to his absence.

“Why did he run away?” he mused.

“He was just looking for happiness.”

Other residents of Block 17 weren’t able to run. Most of those who remained during the war were elderly or disabled. Many were former glassworkers and their families, since the Bucha Glassworks is right across the street.

Sergiy Sadykov, 64, was in his 8th-floor apartment when the fire started.

Sadykov once worked at the factory, but his health had declined and he’d been having trouble walking, so he rarely strayed far from where he lived. When reporters visited Block 17, they found Sadykov’s remains amid the rubble of his apartment.

“His legs were really bad. He stayed in the apartment,‘’ said a neighbor named Lyuba.

“He burned to death in the same apartment.”

Iryna

Iryna, now 65, still remembers the exact day she moved into her new apartment in Block 17: March 7, 1984. She and her family had been on a waiting list for four years before being granted housing.

It was so new the heating hadn’t even been installed, but she was thrilled to have a home so close to work.

Now, the building’s proximity to the glassworks had become a liability.

In late February it was commandeered by Russian soldiers, who set up camp inside.

Residents were terrified of venturing outside for fear of encountering the soldiers. They used their group chat to strategize about what to do if they met one on the streets.

Despite these admonitions, a neighbor named Babak was shot making a run from one entrance of the building to another.

“He ran out of the second section. They shouted to him, “Stop!” said Iryna.

“In a nutshell, he did not stop…. They fired straight at him. That was the first person to die."

Other deaths followed.

Sergiy Semeniuk was killed on an expedition to search for dry firewood. His mother, Halyna, died of cancer with no doctors on hand. Vitaliy Nedashkivskyi never made it back from the grocery store.

Nedashkivskyi — a security guard who lived with his mother, a cleaner — had a passion for cleanliness but a weakness for alcohol. He often helped his mother mop the block’s common areas.

“He was beaten to death, just beaten to death,” Iryna said. “They might have been there at the time, and he came drunk. They just beat him to death with gunstocks or something like that.”

Nedashkivskyi never returned home that day. Locals reported seeing him dead outside the grocery store, but his body was never recovered.

Even if it had been, there would have been no chance of a dignified burial, or any burial at all. The Russians ordered that dead bodies should be left where they fell.

“They said, ‘No, you will not bury them. As long as it’s cold, let them lie there,” recalled Iryna.

After a while, the locals decided to move a number of corpses into an abandoned bus close to Block 17.

“We had a whole cemetery gathered there in the bus."

Emotions were fragile under occupation, and arguments sometimes broke out on Telegram, especially when it seemed like one neighbor was endangering the rest.

Frustrated residents accused the smoker of being a "drug addict,” endangering the lives of everyone on Block 17 for the sake of a hit. The truth was more complicated.

The apartment owner entered the chat to explain:

The "drug addict" was actually Oleksandra's brother, who had been helping put out the fire.

A few days later, bickering broke out again.

Residents had been told to go into blackout mode at night so Russian soldiers wouldn’t start shooting at them.

But one of the families that fled had forgotten to take down a string of flashing Christmas lights. The remaining denizens of Block 17 were furious. They tried to get in touch with the owner to shut them off.

In mid-March, the chat began buzzing with rumors about a pair of young Bucha women who were supposedly collaborating with the Russians.

Memes and internet rumors had accused the two of a litany of wartime sins: drinking and using drugs with the Russian invading forces, sleeping with them, and betraying Ukrainian soldiers by sharing secret information.

But two months later, residents were chastened by how the women had been described. Most of the chatter, it turned out, had been hearsay and gossip.

“The fact is that they were released because [authorities] did not find enough evidence,” said Iryna.

Reporter Yana Korniychuk speaking to residents of Block 17.

Toward the end of the occupation, things got scarier. A new contingent of troops moved into Bucha, and residents quickly found that they were more brutal and battle-hardened than the initial occupiers.

Their observations are backed up by other accounts. A Reuters report from May, citing locals, said a mysterious new commander who arrived in Bucha midway through March. His arrival preceded an uptick in violence, along with other new cruelties.

More reports of violence began to trickle into the chat.

The woman who died that day, Valentyna, was a former nurse in her early 60s who lived in a nearby building. She seemed to lead a lonely life, with her only daughter grown and gone.

She was using a cooking area near Block 17 that residents had set up to prepare warm meals: bricks piled up into a makeshift fire pit.

Startled by a sudden shot, she bolted — forgetting, in her panic, the warning never to run.

“I was shocked,” said Iryna. “It’s not like she was here for the first time. She already knew [not to run], and she still ran. She apparently just did it out of fright.”

“She was a good woman.”

That same week, empty apartments in Block 17 were looted.

Residents shared the news on Telegram, but they were confused about who exactly was doing the looting — Russians (or “Rashists,” as they called them, a portmanteau of “Russians” and fascists” that caught on during the war) or desperate locals.

Even the thousands of messages in the Telegram chat didn’t capture all the horrors visited on the residents of Block 17.

As Mykhailo and Iryna spoke to a reporter, another neighbor, Lyuba, returned home to the block.

Iryna motioned her over and asked if she wanted to share her story — a story that never made it onto Telegram, since Lyuba doesn’t use the app.

Mykhailo and Iryna

Lyuba is well-known on Block 17 for her delicious cooking and her love for her husband, Tolik.

Tolik and Lyuba grew up together and eventually had two children of their own. Tolik worked as a builder; at home, he was a neat freak who shaved with cold water every morning before tucking into a hearty Ukrainian breakfast.

When the war started he changed his routine only slightly, carrying a more abstemious breakfast — buckwheat porridge and tea — to the basement so he could eat without fear of an airstrike.

That’s where Lyuba and Tolik were on the morning of March 29.

“I said, ‘Tolya, take a couple more spoonfuls of buckwheat,'" she recalled. “He ate.”

Lyuba

After breakfast, Tolik walked upstairs to a bench just outside the apartment house to help a neighbor tend to a leg wound.

The man screamed.

“Don’t scream, or they’ll come to finish you!” Tolik told him urgently.

It was too late.

“He was shot as he stood half-bent near the bench," Lyuba said.

"Those bullets are still there.”

Later that day, Russia announced it would withdraw troops from the area around Kyiv, conceding defeat in the war’s first phase.

On March 31, Ukrainian troops recaptured Bucha.

“The cars with our flags drove in first,” Iryna said. “I thought my heart would burst. Our guys, oh my God. We cried so much.”

It would be months before the full extent of the carnage would be known. So many dead bodies lay scattered in the city — every few meters along some stretches of Yablunska Street — that the local police started a Telegram channel of their own to try to identify them.

The final count, the mayor recently announced, was 419.

On Block 17, life tentatively returned to normal.

The H— family returned home in April and turned off their Christmas lights. Mykhailo moved in with his son in a nearby suburb, but he still visits the block.

And after two months, the body of Vitaly Nedashkivskyi, who had died outside the convenience store back in March, was finally recovered and returned to his family.

It had been thrown into a mass grave without his phone and keys, complicating the effort to identify him.

He was recently reburied in a grave of his own in the local cemetery.

On a recent visit to Bucha, a reporter saw tiny sparks of life returning to the neighborhood around Block 17. It was a Saturday evening and small children played while a handful of people walked their dogs outside.

But Block 17’s upper floors are still charred and uninhabitable. And nobody is sleeping easy. Authorities have told all Bucha residents to keep a packed bag close at hand, in case they need to flee in a hurry. Iryna keeps her blood pressure pills, underwear, socks, and warm clothes inside.

“I feel like I’m on pins and needles, like something’s going to happen,” she said. “I hope everything will turn out well."

“But this is life.”